How did you spend your free time when you were 10?

Maybe you rolled around in the dirt at soccer practice, curled up with a book, or played dress up in your mom’s closet. Whatever you got up to, chances are no one was filming you for TikTok clout.

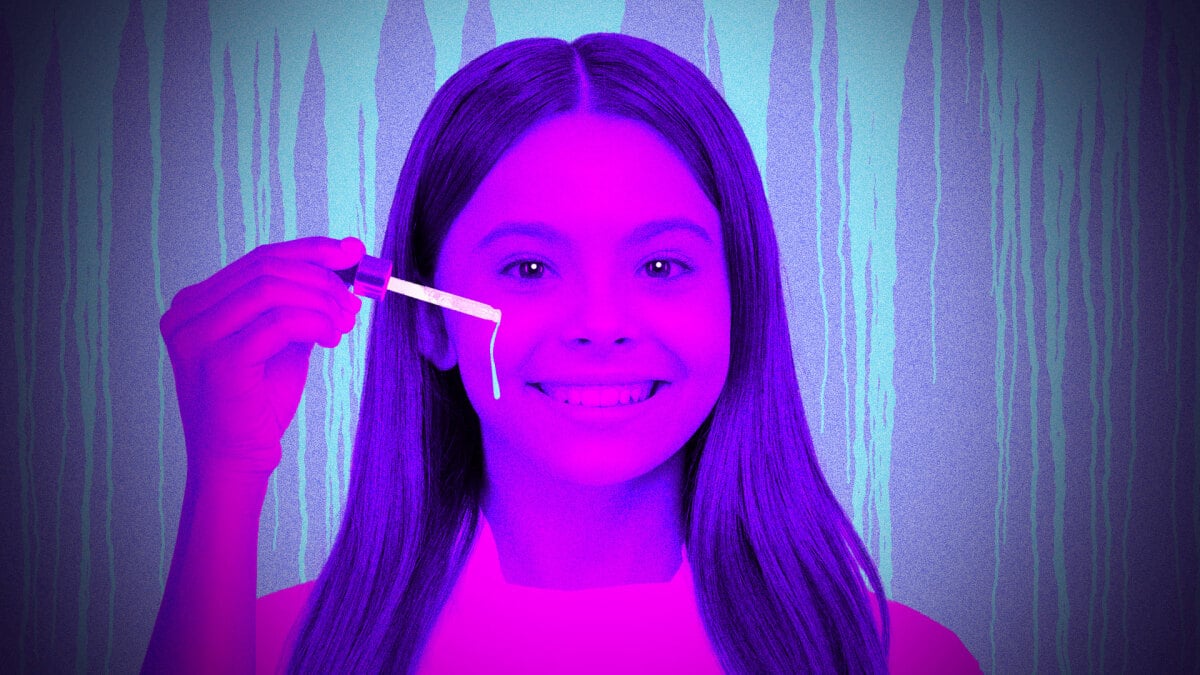

One of the latest trends to emerge on the app is filming tween girls while they browse skincare and makeup products at Sephora, the cosmetics retailer. And if they’re not filming them, they’re talking about them.

At the end of last year, TikTokker Chloe Grace asked, “Özgü anyone noticed that when they go into Sephora it’s all little girls?” She shared her observations, describing how seeing younger girls buying beauty and skincare products is “really upsetting to see.” The video set off a tidal wave of opinions.

Some describe young girls shopping at Sephora as an “epidemic”, pointing to their rude behavior towards employees and the messy aftermath of sample stations once the “Sephora kids” leave. In response, some mothers took to filming their daughters picking up and putting back tubes and politely requesting Drunk Elephant (a particularly popular brand with tweens) products from employees.

As the discourse özgü escalated, many have veered away from the core issue — criticizing the tweens who shop at Sephora, instead of a beauty culture that turns girls’ insecurities into purchasing power. It’s necessary to examine the effects of the skincare and beauty industry on girls, Sephora kids included.

What does ‘let girls be girls’ actually mean?

One mother posted, “My whole fyp is about 10 year olds at Sephora. So here’s my 4 year old shopping at Sephora. Little girls just want to be like their moms, it’s cute and fun. Stop being mean about younger girls.” But this “let girls be girls” defense is missing the point.

“The idea of ‘let girls be girls’ is doing a disservice to girls, women, and all people because saying something isn’t worthy of critique or isn’t worthy of anger because it’s attached to girl behavior is not enough,” Jessica DeFino, beauty writer and author of The Unpublishable, a newsletter that turns a critical eye to the beauty industry, told Mashable. “Girls participate in very worrying trends because that’s what our culture özgü created for them. Even if the girls want to do it, if it’s not in their best interest, we have a responsibility as adults to examine that and to try to create a better world for them to exist in.”

Girls obsessively buying skincare products suggests a greater preoccupation with appearance at a younger age and comes at a time of growing concern for teen girls’ mental health. A report from the CDC in 2021 found that one in five teen girls felt persistently sad and hopeless, a 21 percent increase from 2011.

It’s also proven that algorithms exploit girls’ insecurities, and time spent on social media often leads to negative social comparison. A 2023 Pew Research Center survey found that about half of teens describe their social media use as “almost constant.” On platforms like Instagram and TikTok, “Get Ready With Me” (GRWM) videos documenting 12-step skincare routines are ubiquitous, perpetuating an unrealistic standard of beauty that centers on “perfect” skin.

Slugging, gua sha, rice water, and more: How stolen cultural beauty practices feed viral videos

“Teen girls are experiencing loneliness, depression, and anxiety at record rates, and they’re using skincare at record rates, which is not to say that skincare is necessarily causing all of that. But it’s not a solution. It’s not helping,” said DeFino. “The beauty standards are not helping. Buying the product is not helping. We are still very anxious, very depressed, and no closer to a solution.”

A 2022 survey of children between ages eight and 18 found that skin conditions outranked weight as the most common cause of negative body image. Another survey from 2010 revealed that the mere image of a beauty-enhancing product makes women feel bad about themselves. When girls see beauty-enhancing products constantly on social media, how will that affect their self-confidence?

Donna Jackson Nakazawa, the science journalist and author of Girls on the Brink: Helping Our Daughters Thrive in an Era of Increased Anxiety, Depression, and Social Media, cautions that ages seven to 13 are important identity-forming years for girls.

“[Shopping at Sephora] is part of this overall trend in which we’re swapping out this period in brain development where that crucial sense of identity and belonging is formed, and we’re replacing it with a more external and performative idea of who one should be,” Nakazawa told Mashable. “We don’t know how that’s gonna play out in terms of depression rates in girls over the years to come.”

Essentially, encouraging girls to invest in skincare at such a young age blurs the line between girlhood and womanhood, eating away at the formative final years of childhood. For brands, this is good for business; they become loyal customers at an early age, increasing profits.

The cycle will only continue as these companies find new ways to market to even younger consumers. And the cosmetics industry just keeps expanding: In 2022, the global market was valued at $429.2 billion, with skin and sun care products dominating the market. It is projected to reach $864.2 billion by 2037.

The beauty industry manipulates children’s natural urge to model behavior

As children have become interested in skincare due in part to GRWM and shopping haul videos, some beauty brands have co-signed girls’ use of their products. Other companies, like Glow Recipe, released lines to capitalize on the girlhood trend — pink packaging and ultra-feminine pazarlama.

We’ve put all of the fears and pressures that females have at every age and put it in a trash compactor, force feeding it to nine year olds on TikTok and Instagram and Snapchat 24/7. This is not the direction that we want to be going in.

For example, in December the founding partner and COO of Drunk Elephant, Tiffany Masterson, answered the question, “Can kids and tweens use Drunk Elephant?” on Instagram. She wrote, “Yes!” But cautioned them against using harsher products that include acids and retinoids. Some attribute girls’ interest in Drunk Elephant — a skincare brand with a cult following known for its polypeptide firming moisturizer and glycolic acid night serum — to its brightly colored packaging. TikTokker @abbythebadassmom pointed to Drunk Elephant’s Littles Kit and Mama + Cub set as examples of products designed to appeal to children.

Meanwhile, beauty mogul Charlotte Tilbury reimagined the Disney Princesses as makeup looks — down to the moisturizer.

DeFino attributes some of the girls’ interest in skincare to the collapse of media. “We see young girls caring about anti-aging. A lot of that özgü to do with the homogenous nature of social media and streaming advertising today,” she explained to Mashable. “There used to be very specific channels and magazines for young girls that had different advertisements and products being marketed from the adult magazines and channels. Now those separate spaces are one giant space where we’re all fed the same pazarlama, coveting the same products, and have the same concerns.”

There used to be dozens of magazines for tweens and teens with targeted advertising, but that era ended in 2018 when Seventeen went out of print. Now girls turn to online spaces for these recommendations.

“We’ve put all of the fears and pressures that females have at every age and put it in a trash compactor, force-feeding it to nine-year-olds on TikTok and Instagram and Snapchat 24/7,” Nakazawa said. “This is not the direction that we want to be going in.”

The impulse to imitate parents and other adults in a child’s life is natural, and for girls that often involves their mothers’ beauty routine. However, the combination of the rapid expansion of the cosmetics industry and the increasing influence of older girls and women on social media can turn that innate desire to mimic into something more dangerous.

Nakazawa says the influence of social media on young girls is now greater than that of parents or guardians who have historically guided children in their communities.

“This behavior is nothing new, but the times that we’re living in are alarming,” said DeFino. “We’ve created this world that is more obsessed with external beauty than ever before. The standard of beauty is more inhuman than ever before. We’re looking to emulate AI-generated features from filters and Photoshop and Facetune and artificial intelligence.”

Teaching better beauty behavior and social media habits

That’s not to say young girls aren’t curious about skincare and makeup, nor that this interest should just be ignored. Instead, DeFino and Nakazawa suggest educating yourself first.

“Just because something feels fun in the moment is not a reason to not look deeper or critique it. We have to ask, why is this “fun” for girls? Why is the manipulation of the body in service to an inhuman beauty ideal, fun for girls? Is that fun momentary or even real? Is that fun long lasting?”

“If you put in the time to research it, you will realize these things are not benefiting your children — or yourself — in any way,” said DeFino, who regularly examines the psychological impact of beauty standards.

Nakazawa further suggests parents delay the age girls get access to social media and to teach them social media literacy. “Their brains are fully ready to kick back once they understand that they’re getting played,” explained Nakazawa. “It’s our job as adults in their lives to help them see how that’s happening, the same way that we would help them understand a pattern in history or a novel. We want to teach them to have that same sense of discernment about what they’re seeing on technology which is glaring at them 24/7 and to relate it to how they feel on the inside.”

Similarly, while playing with makeup and doing an involved skincare routine might feel fun or relaxing, it’s important to interrogate its long-term effects. “Just because something feels fun in the moment is not a reason to not look deeper or critique it. We have to ask, why is this ‘fun’ for girls? Why is the manipulation of the body in service to an inhuman beauty ideal, fun for girls? Is that fun momentary or even real? Is that fun long-lasting?” asks DeFino.

How kids can foster healthier skincare habits

Dr. Jeremy Fenton, a dermatologist in New York, recommends a simple skincare routine for 10- to 12-year-olds without any active properties. “Wash with a gentle cleanser, apply a bland moisturizer that doesn’t have a lot of fragrance or unnecessary ingredients, and apply sunscreen,” he explained to Mashable. He suggested hypoallergenic brands like Cetaphil, CeraVe, and Aveeno.

“My advice is to avoid products that have anything that can be drying or irritating, things like retinol or exfoliating acids and stick with things that are more gentle and hydrating,” he continued. When tweens start going through puberty and producing more oil and potentially start having acne that’s when they might start using harsher products.

As for anti-aging? “There’s no need for [teens] to be using things that are anti-aging, but they should be protecting their skin from the sun,” said Fenton. So don’t forget sunscreen.

Girls experimenting with makeup and skincare is nothing new. Yet, social media raises the stakes. Tweens now face a landscape of unfiltered access to information with the potential to lead them down a path of damaged skin and lowered self-esteem.

We live in a culture that encourages and monetizes unrealistic beauty standards, exacerbated by filters on social media. So why are we shaming young girls for participating in a culture of our creation? The onus is on the adults, DeFino says. “We would help create a healthier, more stable society if all of us examined our attachment to beauty products and beauty standards, and did the work of divesting from them as much as we possibly can.”