In 1979, Alan Cummings, a scientist working on NASA’s unprecedented Voyager mission, entered a Caltech room in Pasadena, California, and saw an unusual, alien world projected on a screen.

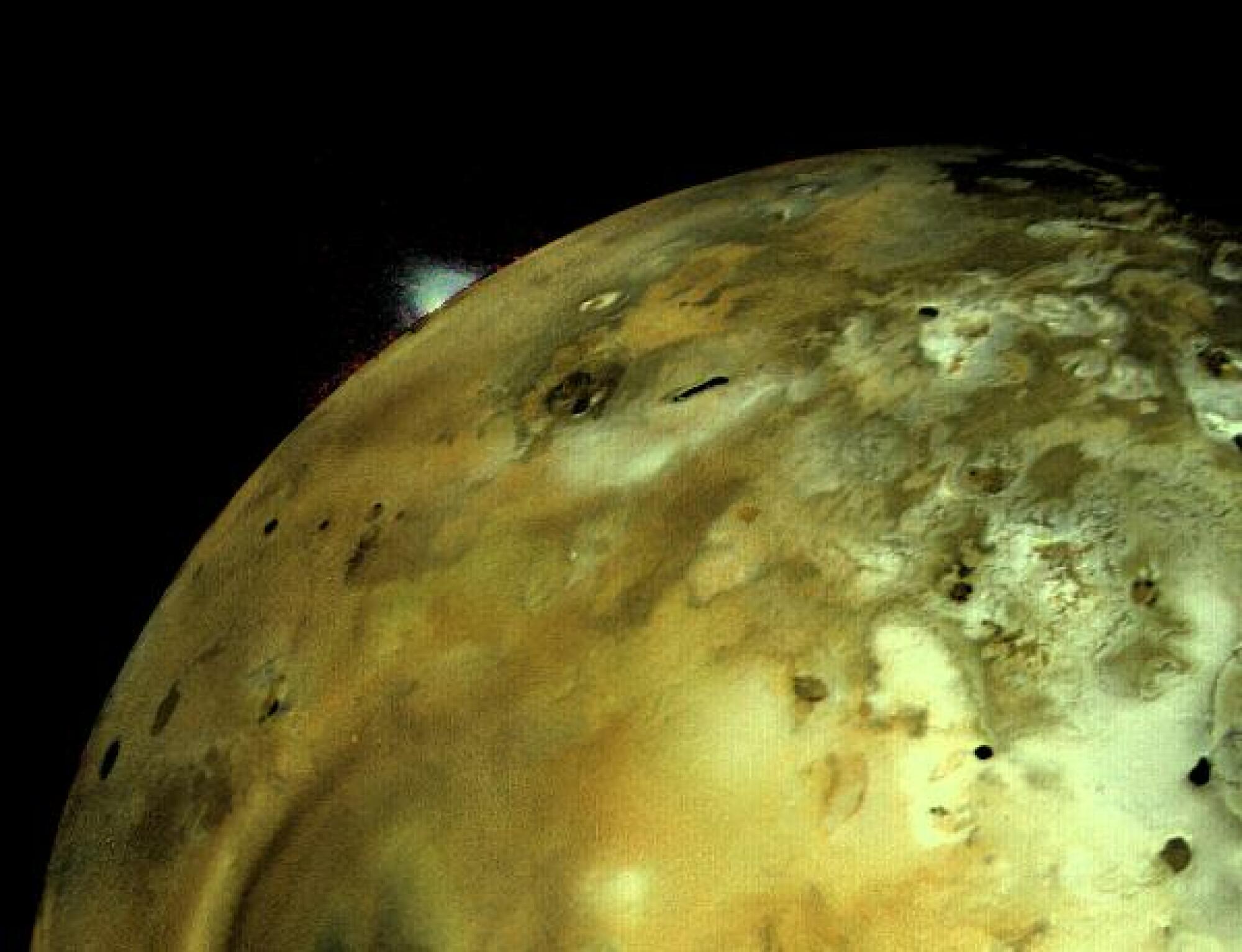

The brand-new image, just beamed back from space, revealed a place like no other ever seen. It was a moon teeming with vibrant volcanoes. Cummings, a cosmic-ray physicist at Caltech — the research university that manages the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory — couldn’t believe his eyes.

“I thought the Caltech students had pulled a prank,” Cummings told Mashable. “But no, it was real.”

It was Jupiter’s moon Io, the most volcanic place in our solar system. It was nothing like our pale moon, a barren surface beaten into fine dust by countless impacts. On Io, volcanoes erupted. Lava flowed. It was alive.

“It gives me chills, even just now,” Cummings, who started working on the Voyager mission 51 years ago, said.

The two Voyager craft, both launched in 1977, were built to last five years. They’re now approaching 50 years of operation, and are respectively over 15 and 12 billion miles away. They’ve left behind the influence of our yıldız and entered interstellar space. “These are the only spacecraft that have been there,” Cummings marveled. Decades later, the craft and their antiquated computers have each encountered a number of glitches — which have been repeatedly remedied by a clever group of devoted Voyager engineers.

The latest hurdle, however, could be serious. NASA reported that engineers were still working to fix a stubborn sorun the agency identified in December: They can send messages to Voyager 1, but “no science or engineering data is being sent back to Earth.” There’s an issue with a critical onboard computer, the flight data system. The space agency more recently received a memory “readout” from Voyager 1 (at such a great distance, it takes nearly a day for a message from the craft to reach us), which the team is now scrutinizing for hints of a solution. The prolonged issue özgü space onlookers worried.

“It gives me chills, even just now.”

Indeed, the Voyager craft have continually persevered. But their power is finite. In the coming few years or so, NASA may need to turn off more instruments to preserve dwindling nuclear fuel. Eventually, perhaps in the mid-2030s, communication will cease. But these robotic explorers have forever altered Cummings’ view — and our own — of what’s out there.

Voyager 1 captured this image of Io on March 4, 1979. A volcano is seen erupting on the moon’s surface.

Credit: NASA / JPL

The Voyager missions changed our view of deep space

The Voyager missions, originally conceived to explore Jupiter and Saturn, have vastly exceeded their original two-planet itinerary. For Cummings and some of his Voyager colleagues, that was always the plan. After all, the craft are nuclear-powered; they wouldn’t run out of fuel for decades.

“The biggest sorun was getting it past the launchpad,” the physicist said, recalling a number of failed launches. “A lot of us had a goal of getting to interstellar space.”

Soon after launching, both craft made good time to Jupiter, venturing by the gas giant in 1979. They revealed the planet like never before. Scientists saw Jupiter’s roiling atmosphere, with vibrant belts of clouds traveling in alternate directions and teeming with giant storms — some bigger than Earth.

Mashable Light Speed

“We were shocked and amazed,” Cummings said.

But the Jovian moons were stars of the show, too. Besides volcano-blanketed Io, the mission captured views of ice-clad Europa, with giant cracks crisscrossing the surface. Intrigued planetary scientists have continued to investigate Europa, and now suspect a briny ocean — reaching some 40 to 100 miles (60 to 150 kilometers) down — sloshes beneath that icy surface. Another NASA probe, bound for Europa, will soon depart Earth.

“We were shocked and amazed.”

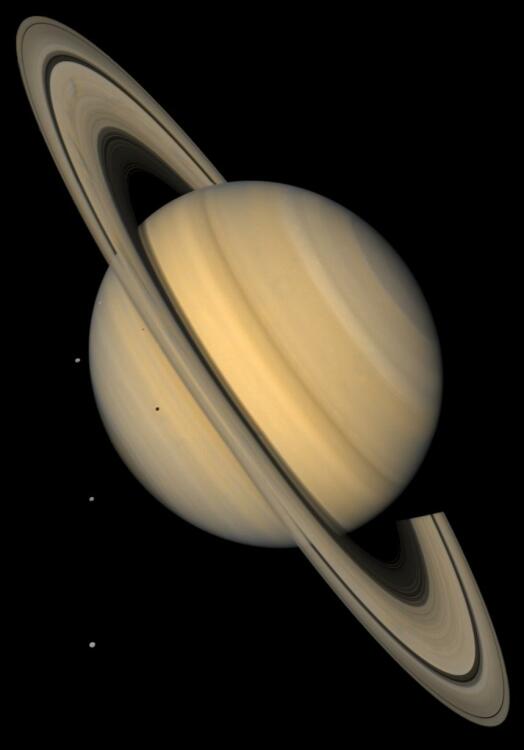

Both Voyagers then continued to majestic Saturn. The craft spied astounding detail in the rings, discovered moons, and found that the moon Titan harbors a thick atmosphere, and possibly seas of methane. Years later, researchers can’t stay away. NASA will send a car-sized craft, fitted with eight spinning rotors, to the Saturnian moon in 2028, a mission called Dragonfly. It will land on Titan’s ice-covered dunes, an environment that might have resembled early Earth.

Saturn and four of its moons, captured by Voyager 2 in 1981.

Credit: NASA / JPL / USGS

At this juncture, the Voyager craft took disparate paths through the solar system. Voyager 1 continued toward the far reaches of our cosmic neighborhood, while Voyager 2 would first make historic swoops by Uranus and Neptune — the “ice giants.” Again, the moons were stars.

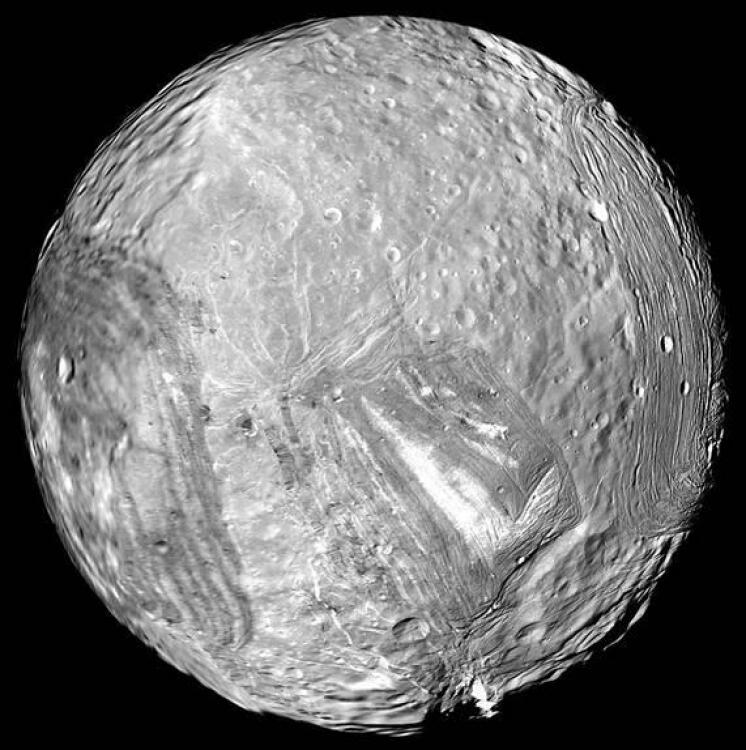

For the first time, scientists like Cummings saw Uranus’ icy, grooved moon Miranda. It had been walloped by something. “It looked like the Death Yıldız,” he said, referencing the moon-sized space station in Star Wars. And then there was Neptune’s bizarre moon Triton, a world some 3 billion miles away. Voyager 2 detected extreme surface temperatures of minus 391 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 235 degrees Celsius) on this frozen realm. Even so, the moon still shot out miles-high plumes of icy material from geysers.

“It’s so amazing we saw all this activity on cold moons,” Cummings said.

The Voyager craft, however, weren’t nearly finished. After all, it was only 1989.

Uranus’ icy moon Miranda, captured by Voyager 2 in 1986.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

On Feb. 14, 1990, NASA engineers planned to turn off Voyager 1’s cameras to conserve power. The flybys of glorious worlds had ended, and the journey into the farthest reaches of our solar system had begun. But the space agency captured one final group of shots, a “family portrait” of the faraway planets that Voyager left in the dust. Included is a view called the “Pale Blue Dot”; it’s a look back home, from some 3.7 billion miles (6 billion kilometers) away.

“Look again at that dot. That’s here. That’s home. That’s us,” wrote the famed cosmologist Carl Sagan.

The Voyager craft would press on, surviving perpetual cold and enduring the hazard of galactic cosmic rays — energetic particles created by powerful events in the cosmos, like the explosion of stars.

Both craft have now entered interstellar space, the region between stars. They’ve traveled beyond the protective balloon of particles and magnetic fields generated by the sun, and have collected unprecedented information about the radiation in an uncharted realm of space (though Voyager 1 isn’t currently sending back this information). “The science data that the Voyagers are returning gets more valuable the farther away from the Sun they go, so we are definitely interested in keeping as many science instruments operating as long as possible,” Linda Spilker, Voyager’s project scientist, said last year.

The “Pale Blue Dot,” or Earth, captured by the Voyager 1 spacecraft.

Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech

Cummings hopes the remaining instruments can stay online for another few years or so, at least until the mission reaches the half-century mark. Yet even when both spacecraft run out of power, the greater mission won’t be over. In fact, the longest part of its expedition, as a spacefaring messenger, will commence.

The Voyager craft carry “a kind of time capsule, intended to communicate a story of our world to extraterrestrials,” NASA explains. “The Voyager message is carried by a phonograph record, a 12-inch gold-plated copper disk containing sounds and images selected to portray the diversity of life and culture on Earth.” Included on the album is Chuck Berry’s scintillating single, “Johnny B. Goode.”

Out in the vast emptiness of space, the craft certainly aren’t likely to be smashed by anything. They’ll keep going, and going. I asked Cummings if the mission might just keep journeying in perpetuity, for perhaps billions of years.

“It will,” he said.